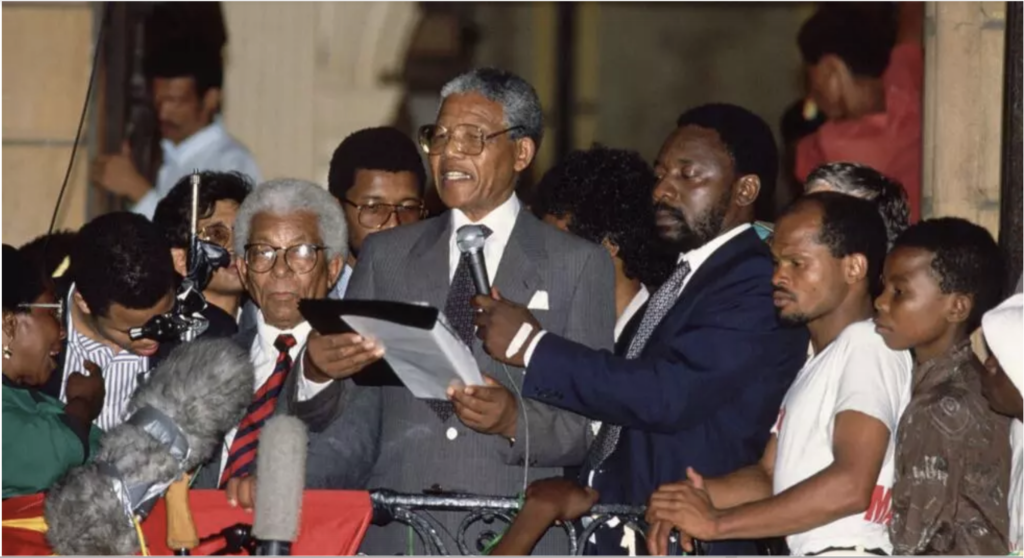

Nelson Mandela addresses the crowd from the balcony of City Hall in Cape Town, South Africa, on February 11, 1990. To his right is Walter Sisulu, his comrade-in-arms who had been released a few months earlier, and to his left is Cyril Ramaphosa, general secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and now President of South Africa (since 2018). © Peter Turnley/Corbis/VCG via Getty On February 11, 1990, Nelson Mandela, the most famous and oldest political prisoner in the world, took his first steps as a free man. Millions of people around the world who witnessed the event live on their small screens discover the smiling but slimed and aged face of the one whose last known images were taken in the early 1960s. This great report returns to the little-known conditions of this liberation. By Nicolas Champeaux.

February 11, 1990. Here is Nelson Mandela in front of cameras around the world, and he raises his fist to the sky. He is free, finally, after 27 years in detention. For anti-apartheid singer Johnny Clegg and millions of South Africans, Mandela was a promise who had been cut off the wings: “It was fantastic. For me, it was as if the clouds had dissipated to make way for heaven. When he came out and raised his hand to greet everyone, he gave off a certain composure and expressed confidence that the story would unfold quietly and that we would succeed. I am one of the generations that grew up in the late 1960s, 1970s and 1980s and who had never seen Nelson Mandela. We knew what his name evoked, but we could not associate his name with an image. At the time, it was illegal to carry a photo of Nelson Mandela, it was a criminal act. It is this notion that I develop in my song Asimbonanga. We had never seen Mandela. While for us, the simple sound of his name evoked the promise of a new South Africa”.

Ironically, Mandela, over the 1980s, had also become the providential man in the eyes of the leaders of apartheid, a regime in distress. Isolated on the international stage, plagued by the protesting bustle of black townships, in the residential suburbs too, more and more young whites are boycotting compulsory military service. They do not want to be associated with the increasingly fierce repression of demonstrations organised by black South Africans whose only claim is the right to dignity.

The regime then resolves to negotiate in total secrecy. During the two years before his release, Justice Minister Kobie Coetzee and the head of the Secret Service Niel Barnardont met with Mandela. Barnard remembers Frederik de Klerk was put in confidence only following his accession to the presidency in August 1989: “De Klerk was furious because he had not been informed of the ongoing negotiation process and up to a certain point, I understand it. He was a prominent minister in the Botha government. So de Klerk was extremely irritated that, supposedly behind his back, secure officials had been at the controls of the negotiations with Botha’s endorsement. But I was deeply convinced that the members of the government should not be informed. And I convinced Botha. I told him if you inform them, the negotiations will fail the next day.”

In 1982, Nelson Mandela and other prominent ANC (African National Congress) leaders, including Walter Sisulu and Ahmed Kathrada, were transferred to Pollsmoor High-Security Prison in Cape Town. Kathrada had also been sentenced to life in prison after the Rivonia trial. He had just spent 18 years in custody at Robben Island alongside Nelson Mandela. But in Pollsmoor, the latter did not tell him about his first encounters with the enemy: “The day he was brought back to prison after his operation in the hospital, the senior officers told him, ‘Mandela, we will separate you from your co-prisoners. Our immediate reaction was to protest. But Mandela told us, “No, don’t say anything, maybe something good will come out of it.” That’s when we realised that he had something on his mind. But we had no information. Mandela deliberately took the first step without informing us. He was a Democrat. He was not sure that we would support him in his approach. And if the majority had been against it, he would have had to resign himself. He says it in his biography. He wanted to take the initiative alone because there are times when leaders have to show the way. And then Mandela was going to be isolated here, and he often said, “There is one thing that prison offers, it’s time to think”.

Niel Barnard: “The first meeting took place in 1988 in the office of the commander-in-chief of Pollsmoor prison, on May 23, I think. Mandela is coming. He was dressed in his prisoner’s uniform and had boots on his feet. But I must say that even in this outfit, we could see that he was a proud man. He exuded a certain grandeur and was endowed with an incredible personality. We immediately addressed the three questions that I was responsible for submitting to him. First, was he interested in a political solution negotiated within a constitutional framework? Secondly, would he agree to give up his movement’s military campaign? And thirdly, what were his views on the future role of the Communist Party? It was a good meeting. We decided to continue the process, and for two years, we had intense negotiations on these three topics. You should know that in the second step, when Mandela was transferred to Victor Verster, we deliberately authorised him to meet his co-detainees so that he could inform them because we knew he was under pressure. The others had to ask themselves, “Will he seal a secret agreement, and can we trust him?” ”

Mandela took leading roles in the liberation movement with the Youth League, then as a chief volunteer of the civil disobedience campaign and also at the head of the armed branch of the ANC, Umkhonto we Sizwe (“spearhead of the nation”). He especially earned his stripes during his speech at the Rivonia trial, while he and his co-defendants risked the death penalty. Mandela said he was ready to die for the cause of a free and democratic society.

Mac Maharaj, Nelson Mandela’s protégé at Robben Island, speaks of his mentor as a natural leader and a fine strategist who inspires unfailing confidence: “Mandela was not a leader simply because he held the position of leader, but because he reaffirmed his leadership daily. This was the case in prison in particular. I’ll give you an example. We worked on the quarry; the prisoners went there on foot, and we were supervised by armed guards, two in front, two behind and two on each side. One morning, the guards were particularly aggressive. They were unleashed and screamed in our ears, “Walk faster!” We had the impression that they wanted to beat us up. And there, the prisoners began to whisper an instruction to each other. Mandela says you have to walk slowly. I said to myself, but who does he think he is? My legs tell me to walk fast because I don’t want to be hit on. And that’s where we saw Mandela sneaking among the prisoners to win the first rank. And suddenly, I realised that I had slowed down the pace. Why? Because the very first row, led by Mandela, walked slowly. So, Mandela was there, on the front line of reprisals and threats. He had grasped that to convince his people to behave in a certain way in a threatening climate, he had to be the most exposed to danger, at the front. He also showed that it was useless to answer the guards and tell them to go to hell. And so, all the rows walked slowly. The guards screamed until they didn’t know what to do. I give this example because it’s one thing to climb a platform and order your troops to fight. But when the battle is in full swing, behaving as a true leader is ensuring the loyalty of your troops by exposing yourself on the front line.”

Mandela, before continuing his talks with the government, wished to inform the movement. He asks his lawyer, Georges Bizos, to go to Zambia to alert Oliver Tambo, the head of the ANC in exile. Nelson Mandela was eager to negotiate directly with the president. But Peter Wilhelm Botha suffered two heart attacks. The secret meeting finally took place in July 1989. Neil Barnard: “We took Mandela to the presidential office in Tuynhuys, Cape Town. The National Intelligence Service was in charge of the operation. So I took care of the relocation of the Victor Verster prison to Tuynhuys. We arrive in Tuynhuys. The security services of the presidency had to see Mandela, but I don’t think they recognised him because, as intelligence chief, I often brought African heads of state to the palace for meetings with President Botha, and I had good relations with the security police. They knew they didn’t have to ask me who I was introducing into the building. So that’s it, we brought Mandela back to the nose and beard of security for the meeting. Amazingly, as older people often do, Mandela and Botha spent some time convincing each other that they were in perfect health. Then they talked about Africa, the Afrikaners and the Anglo-Boer War. It was a very courteous meeting, centred above all on the personalities of each other. They talked about Africa. It was a very good meeting.”

Nelson Mandela proved to be a formidable negotiator. His interlocutors will say that his heat was disarming, and at Robben Island, he had learned the language of the enemy, Afrikaans. Mac Maharaj: “Mandela persuaded me to study Afrikaans. I was opposed to it, but he relied on a military case and asked me, “How are you going to lead the enemy general to fall into the ambush you set him? To succeed, you must understand the general’s way of reasoning. So if you attack a base A, you know in advance that it will move its forces to point B, and that’s where you’ll have set your ambush.” So, Mandela told me you have to understand them. But for that, you need to know their history, their language, their culture and their value system.”

In December, Mandela returned to the Cape presidential office. We make him enter in secret through the garage again. He met Botha’s successor, Frederik de Klerk. The two men promise to see each other again. Mandela then lived in a house in the Victor Verster prison. He could read the newspapers and receive visits. He also enjoyed the progress of household appliances, with a certain fascination for the microwave oven. Meanwhile, the intelligence services travelled to England and Switzerland to meet the leaders of the ANC in exile. President Frederik de Klerk, even before his inauguration, had promised to completely transform South Africa. Words are immediately followed by concrete actions. Authorities are giving the green light for the great peace march in the streets of Cape Town in September. The fall of the Berlin Wall, two months later, convinced the government to move up a gear. He can no longer claim to fight against the ANC to stem communist expansion. On February 2, 1990, de Klerk announced the imminent release of Mandela and the lifting of the ban on the ANC.

Mandela’s release takes place in haste. His supporters have less than 24 hours to organise the ceremony. South Africans give Mandela a triumphant welcome, but thugs mingle with the crowd. The tension threatens. Neil Barnard, the head of intelligence of the president of Klerk: “There was much looting that day and little was said about it. This was one of the major concerns. It is for this reason that his first speech was organised in Cape Town and not in Soweto because it would have been extremely difficult to keep order there. It was a huge challenge for us. Mandela believed that his marshals would be able to control the crowd, but this was not the case. It was very delicate. Imagine what would have happened if the celebrations had degenerated into chaos. We should have imposed the state of emergency again, requisitioned the military perhaps, and all negotiations would have fallen by the wayset. We might even have been forced to arrest Nelson Mandela again. But fortunately, everything went well.”

Amandla! Awetu! Amandla! “(“Power is ours! “) In Cape Town, on February 11, from the balcony of the town hall, Mandela called on his supporters to continue the armed struggle until the surrender of the apartheid regime. No bitterness or spirit of revenge in his speech. However, he invited the whites to bring their stone to the edifice of a new South Africa. Twenty years later, Ahmed Kathrada, one of Mandela’s most faithful companions, welcomes the spirit of reconciliation that blew on February 11 after such a long journey: “There is a whole story behind February 11. It goes back to his first meetings with people on the other side and his first demands: “First release all other political prisoners, lift the prohibitions that weigh on our organisations,” he said. I remind you that we are talking about the people who were responsible for the worst laws in the country. We had to talk to them and it was not easy. They wanted to impose a whole bunch of conditions on us. They told us, “We don’t negotiate communists in your delegation”. Mandela replied, “We have not chosen the members of your delegation. There, you are talking about our delegation, you are not going to compose it in our place.”

It was a long-term test. But in the end, he succeeded. Even if we have made concessions, so have they. That’s why we accepted the concept of an interim government in the first five years. They were assured that their police chief and army chief would be able to stay on the spot. In our camp, there are people, even today, who criticise us for having conceded too much. But most often, it is young people who have not lived this time. They think it was a military victory and that we could say to the enemy, “Here, we won”. But it wasn’t that at all. It was a negotiated solution. I think that from an overall point of view, it was even a success. People have accepted to share the same country, the same flag, the same national anthem. That’s the meaning of February 11. It’s freedom, even for our white compatriots. They were bad about themselves before. When they were abroad, they hid their South African passport because, at the time, the whole world was on our side. So they were told, “We have freed you too. Now, you can proudly show your South African passport, proudly wave your South African flag.” We brought them security and freedom, but above all, we offered dignity to all South Africans. And that’s the lesson, the legacy of February 11″.

Nathalie Amar: Nicolas Champeaux is online from the Cape. Nicolas, what is striking when listening to your report is that during these years in prison, Mandela and the other leaders of the ANC continued the fight in a methodical and very disciplined way.

Nicolas Champeaux: Yes, Mandela and his people behaved, as soon as they arrived, as if the world of the prison was a reduced version of the world. As a result, they continued to fight for their right to dignity. They continued to fight discrimination in prison. They protested, for example, when inmates of Indian origin received more generous food rations than blacks. In addition, they scrupulously respected the rules of operation of the ANC. The decisions were collective. They discussed everything, durations, hunger strikes, for example. Mandela and his people also invented clever ways to issue instructions aimed at destabilising the regime and eventually forcing it to negotiate. The message of this 20th anniversary is very clear. The ANC says the struggle has freed Nelson Mandela. It was not a gesture of kindness, a gift from Frederik de Klerk. It was the South African people who opened the gates of the Victor Verster prison twenty years ago, day by day.

What must be said, then, Nicolas, is that this February 11, of course, not everything is settled with the release of Mandela and negotiations with Klerk’s power continue.

And yes, because Mandela said it on February 11, 1990, it was still necessary to liberate the South African people and allow them to choose their political leaders in the future and to vote. So the ANC boasts of having been able to impose the timing and rules of the negotiations, but Mandela was still negotiating with men who were still masters of all the instruments of power. It was a real challenge. And Mac Maharaj, who we hear in the report, repeated it this morning: “This march, this second march was a march towards the unknown”.

“Mandela, the secret history of a liberation”, a great report by Nicolas Champeaux. Directed by Marc Minatel.